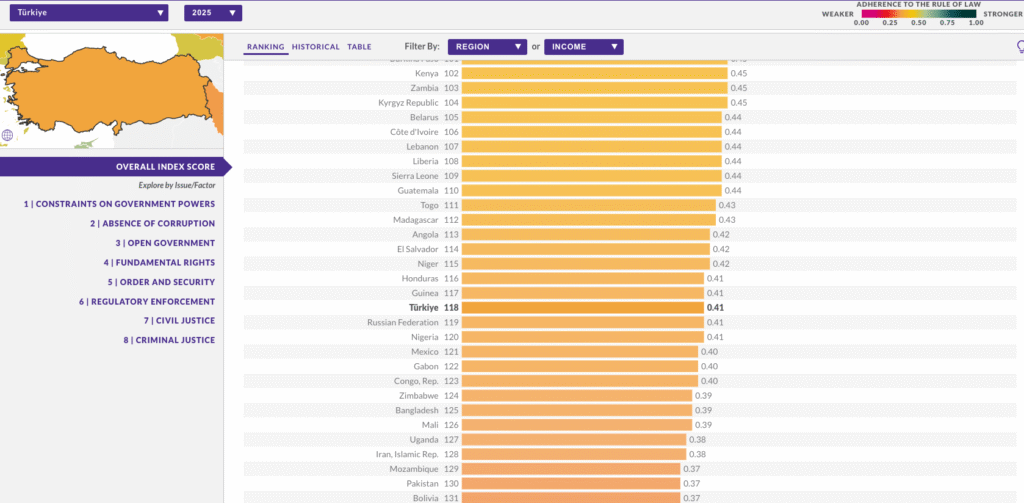

Turkey was ranked 118th among 143 countries in the 2025 “WJP Rule of Law Index” published by the World Justice Project on Wednesday, dropping one place compared to last year.

The country remained near the bottom both globally and regionally, placing 14th out of 15 countries in the Eastern Europe and Central Asia region, and 37th among 41 upper-middle income countries.

The index measures countries’ performance across eight categories: constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice and criminal justice.

Turkey has experienced a sharp decline in the rule of law over the past decade. Ranked 80th in 2015, it has since fallen 38 places. The decline accelerated after a coup attempt on July 15, 2016, which led to widespread purges of government institutions and restrictive measures, pushing Turkey down 19 places to 99th that year alone.

In the “Fundamental Rights” category, Turkey ranked 134th, reflecting deterioration in areas such as absence of discrimination, right to life and security, due process of the law, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom of belief and religion, freedom from arbitrary interference with privacy, freedom of assembly and protection of fundamental labor rights. In this category Turkey has fallen 38 places over the past decade.

Turkey also ranked 136th in “Constraints on Government Powers,” which measures the judiciary’s role as an independent check on the government. In this category Turkey has fallen 41 places in the last 10 years.

The erosion of the rule of law in Turkey over the past decade began after a failed coup in 2016. In its aftermath the government launched a sweeping crackdown on the Gülen movement, inspired by the late Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen, whom it accuses of orchestrating the attempted coup.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been targeting followers of the Gülen movement since corruption investigations in December 2013 implicated him as well as some members of his family and inner circle. Dismissing the investigations as a Gülenist coup and a conspiracy against his government, Erdoğan began to target the movement’s members. He designated the movement as a terrorist organization in May 2016 and intensified the crackdown on it following the abortive putsch in July of the same year that he accused Gülen of masterminding.

More than 4,000 judges and prosecutors were removed under the pretext of an anti-coup fight. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) replaced the purged judiciary members with young and inexperienced judges and prosecutors who have close links to the AKP. Following the coup attempt and the transition to a presidential system of governance in 2018, the Erdoğan administration has operated largely without political or judicial checks and balances.

Throughout the decade the Erdoğan government has escalated its repression of perceived adversaries and dissidents, with the Gülen movement remaining a primary target. Numerous incidents in recent years have raised concerns about the weakening of judicial independence and the use of the judiciary as a tool by the Turkish government against critics and opposition figures.

Following the opposition’s victory in local elections on March 31, 2024, a series of investigations targeted mayors from the main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Peoples’ Equality and Democracy Party (DEM Party), while trustees were appointed to some municipalities. The arrest of 17 mayors from the CHP, including Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, President Erdoğan’s main political rival in the 2028 presidential election, since March further reinforced the perception that the judiciary was being used to serve government policy objectives.

Journalists have also faced investigations, while pro-opposition or critical media outlets have been subjected to bans, fines and trustee appointments, measures widely criticized as violations of fundamental principles of law and freedom of expression. Similarly, artists, actors and managers expressing or sharing dissenting views are investigated or arrested. Ordinary citizens criticizing the policies of the government have been accused of “insulting the president” and have faced prosecution and detention.

Even criticism directed at the judiciary itself has resulted in criminal proceedings, as in the recent case of three journalists who were sentenced for a report on Istanbul’s chief public prosecutor Akın Gürlek, notorious for his rulings against government critics.