Dissident Turkish journalists in Germany have received threats on social media over the past week from people inviting them to Turkish consulates, implying they would share the fate of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, who was killed in the Saudi Consulate General in İstanbul on Oct. 2.

Dündar, the former editor-in-chief of the Cumhuriyet newspaper, fled to Berlin following a controversial coup attempt in Turkey on July 15, 2016. He has been sentenced to five years, 10 months in prison on charges of disclosing confidential state information and espionage. A Turkish court last week requested that Interpol issue a Red Notice for his arrest.

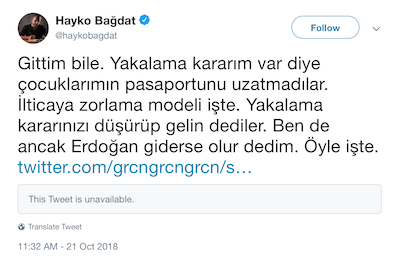

Journalist and commentator Hayko Bağdat also received a similar threat on Twitter, but that message was later deleted. Bağdat, a Turkish national of Armenian descent, also moved to Germany after the coup attempt.

Dündar, in an article for the German Die Zeit newspaper on Wednesday, said mafia boss Peker had also threatened Turkish academics who signed a 2016 petition calling on Turkey to de-escalate a conflict with Kurdish armed groups in the country’s Southeast. Peker said the academics should drown in their own blood.

Dündar said a commentator working for a pro-government Turkish television channel also joined the debate after he received a threat on Twitter. “The followers of Ogün Samast are ready, waiting. One day, all of a sudden, what is needed can be done,” the commentator said to Dündar.

Samast killed Hrant Dink, an Armenian journalist and the founder of the Agos newspaper, in front of his office building in İstanbul in 2007.

“In fact, I should thank both people that sent me those messages. I would not be able to explain the similarity between the approaches against Turkish and Saudi dissidents that clearly, no matter how many articles I wrote on the subject,” Dündar said.

He said such people were emboldened to openly make such threats due to the Turkish government’s policy of impunity. “Would you believe those who invite dissidents to the Turkish consulate in Germany when they condemn the Saudis for eliminating dissidents inside the Saudi consulate?” Dündar said.

Turkey is ranked 157th among 180 countries in the 2018 World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders (RSF). If Turkey falls two more places, it will make it to the list of countries on the blacklist, which have the poorest record in press freedom.

Turkey is the biggest jailer of journalists in the world. The most recent figures documented by SCF show that 237 journalists and media workers were in jail as of October 7, 2018, most in pretrial detention. Of those in prison 169 were under arrest pending trial while only 68 journalists have been convicted and are serving their time. Detention warrants are outstanding for 148 journalists who are living in exile or remain at large in Turkey.

Detaining tens of thousands of people over alleged links to the Gülen movement, the government also closed down some 200 media outlets, including Kurdish news agencies and newspapers, after a coup attempt in Turkey on July 15, 2016. (SCF with Ahval)