Turkey has introduced sweeping changes to its mining permit system that put the final decision-making authority under the presidency, a move environmental groups and legal experts say will weaken oversight and accelerate ecological destruction, Turkish Minute reported, citing the state-run Anadolu news agency.

The regulation, titled “Procedures and Principles of the Mining Permits Board,” was published in the Official Gazette on Thursday and took effect immediately.

The regulation, signed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, establishes a Mining Permits Board at the presidency with the power to grant approvals for new mining sites, expansions and operations in cases where ministries or other state agencies had previously refused permission.

Under the new rule, the board will convene under the chairmanship of a vice president appointed by the president. Its members will include the ministers of environment, energy, treasury and industry along with other ministers directly tied to the permit under review.

The new arrangement concentrates power at the top while reducing the role of independent agencies, local administrations and technical institutions.

The regulation says that when permits for Group IV minerals, which covers Turkey’s most commercially valuable metals and all radioactive mineral resources, are denied by the relevant authority, the energy ministry can apply to the board, which will issue the “final decision in line with superior public interest.”

Group IV includes iron, copper, gold and zinc as well as uranium, thorium and other radioactive minerals. The category of strategic minerals covers rare earth elements, including deposits in Eskişehir’s Beylikova district that Ankara has promoted during talks with Washington.

Critics say the measure could nullify court rulings or administrative rejections issued in response to objections from local communities and environmental groups. Lawyers warn that the arrangement is designed to remove legal obstacles faced by domestic and foreign mining companies.

Lawyer Arif Ali Cangı told Turkish media that the board establishes a “non-questionable authority” and places all power under the presidency, arguing that overriding decisions made by ministries, public agencies and local administrations violates the constitutional principle of administrative integrity.

Another lawyer, İsmail Hakkı Atal, said the rule bypasses the General Directorate of Mining and Petroleum Affairs and the General Directorate of Forestry, adding that the change reflects “the fear of prosecution among [ruling Justice and Development Party] AKP-appointed bureaucrats who hesitate to sign mining approvals.”

The overhaul follows a series of legislative changes in June that environmental groups labeled the “super plunder” and “super permit” laws, which shortened review periods in environmental impact assessments and allowed companies to begin operations before final environmental reports were completed.

The amendments also made it easier to classify farmland, forests, olive groves and pastures as mining zones.

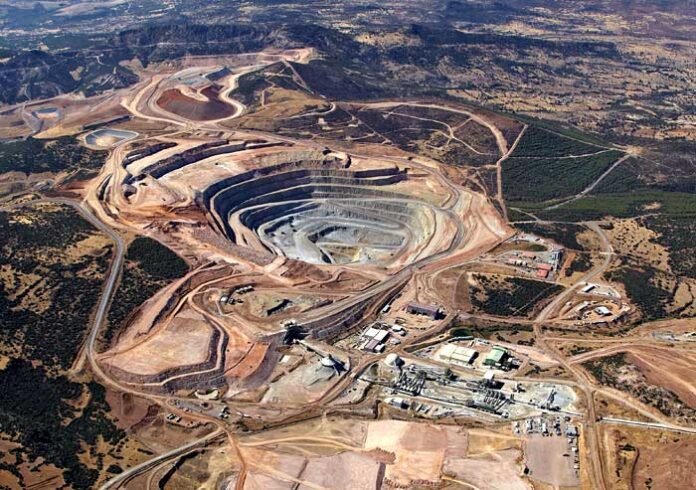

Environmental organizations dispute the government’s claim that the new system will speed up investment. TMMOB Chamber of Environmental Engineers chair Muaz Özkaya said the regulation “invites ecological destruction under the guise of public interest” by allowing single-signature approval for mining in forests, agricultural lands and water basins.

Greenpeace Turkey campaigner Zehra Funda Mobil warned that disasters such as Soma and İliç have shown “the consequences of weak oversight” and that consolidation of control under one authority could heighten risks.

The 2014 Soma coal mine disaster in the western province of Manisa, which killed 301 workers, remains the country’s worst industrial accident and exposed chronic failures in oversight, inspections and enforcement.

More recently, the 2024 cyanide-laden landslide at the Anagold gold mine in İliç in eastern Turkey buried nine workers alive and raised fresh questions about regulatory negligence, political protection for mining companies and gaps in environmental monitoring.

These incidents have unfolded against a backdrop of growing public resistance to mining and energy projects.

In 2023 local villagers and environmental activists occupied the Akbelen Forest, inland from the Aegean resort town of Bodrum, to defend it from an energy company that runs a nearby coal mine.

At the time Erdoğan dismissed protesters as “marginals,” saying new coal basins were needed for the country’s power plants as existing reserves were close to depletion.

Turkey ratified the Paris Climate Agreement in 2021.

Activists say Turkey has enormous renewable energy potential and does not need to rely on coal to produce electricity.