Turkey was ranked 149th among 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) 2022 World Press Freedom Index, with the prominent press organization warning about rising authoritarianism in the country and declining media pluralism, Turkish Minute reported.

Turkey’s 2022 ranking on the RSF index is up from the 153rd last year; however, RSF Turkey representative Erol Önderoğlu, in remarks to Deutsche Welle’s Turkish edition, interpreted the minor change for the better not as a result of the improvement of freedom of the press in the country but as a result of the war fought by civil society and press organizations for more press freedom.

RSF released its “2022 World Press Freedom Index: a new era of polarisation” on Tuesday, which coincided with World Press Freedom Day. It assesses the state of journalism in 180 countries and territories.

“Authoritarianism is gaining ground in Turkey, challenging media pluralism. All possible means are used to undermine critics,” said the press organization.

RSF said since 90 percent of the national media is now under government control, the public has turned, during the past five years, to critical or independent media outlets of various political persuasions to learn about the impact of the economic and political crisis on the country. It cited local TV channels such as Fox TV, Halk TV, Tele1 and Sözcü and international news websites such as BBC Turkish, VOA Turkish and Deutsche Welle Turkish as examples.

According to RSF, as the 2023 election approaches, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan “hyper-presidency” has stepped up its attacks on journalists in a bid to deflect attention from the country’s economic and democratic decline and to shore up its political base.

Through a referendum in April 2017 Turkey switched from a parliamentary system of governance to an executive presidential system that granted Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) sweeping powers and was criticized for removing constitutional checks and balances, thus leading to a further weakening of Turkish democracy.

“However, tactics such as near systematic censorship on the internet, frivolous lawsuits against critical media outlets or the misuse of the judicial system have, until now, enabled Erdoğan to restore his popularity rating, while he continues to be embroiled in a major case of corruption and political clientelism,” RSF says in the index.

Turkey is scheduled to hold presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023.

According to the Turkish Journalists’ Association (TGC), there are currently 28 journalists behind bars in Turkey; however, other media organizations estimate the figure to be higher.

Legal framework

In its report RSF also said discriminatory practices against critical journalists and media outlets, such as stripping them of press passes, are commonplace in Turkey, while journalists face various obstacles to performing their jobs independently.

“Judges who do the government’s bidding are trying to limit democratic debate by censoring online articles tackling corruption and similarly sensitive topics. This makes it hard to publish quality reporting. Some journalists have nonetheless tried to remain faithful to their mission to report the news with complete independence, and they are demanding recognition of a ‘media ombudsman’.”

Economic context

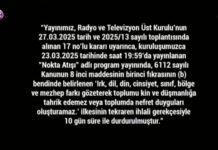

According to RSF, public and private sector companies allied with the AKP government endanger media pluralism by channeling ads and subsidies to media outlets that give them favorable coverage. The Press Advertising Council (BIK) uses the allocation of state advertising to put financial pressure on recalcitrant dailies, while the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK) helps to weaken critical TV channels economically by imposing heavy fines. Some newspapers have had to reduce their number of pages because of the price of paper.