Fifteen Canadian citizens – including academics, journalists, real estate agents and a part-time taxi driver – have been named as suspects in a Turkish “terrorism” investigation for supposed criminal activities such as writing or promoting articles supportive of the Turkish president’s rival, or downloading a messaging app that was popular among critics of the Turkish government, Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail reported.

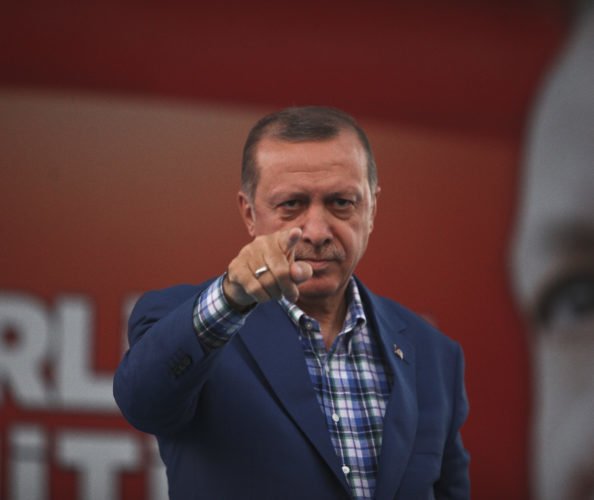

Documents filed in a Turkish court, and obtained by the Globe and Mail, show that Turkey’s national intelligence agency collected personal information about the 15 suspects, including home addresses and work histories. The monitoring of the 15, most of whom are citizens or residents of Canada who haven’t travelled to Turkey in years, provides a rare glimpse into President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s suppression of followers of Fethullah Gülen, a dissident cleric whom the Turkish government blames for a 2016 coup d’état attempt in the country.

Tens of thousands of people have been jailed in Turkey over suspected affiliations with Mr. Gülen, a crackdown that the documents show involves Canada as well.

The information collection was carried out last year at the request of the chief prosecutor’s office in Ankara. In a Feb. 14, 2019, letter, the chief prosecutor asked the national intelligence agency to collect the suspects’ fingerprints and banking information, and said that search and seizure warrants should be prepared “as and when needed,” suggesting the 15 Canadians would be arrested if they ever returned to Turkey. Other documents are dated as recently as Jan. 16 of this year.

Kerim Uras, Turkey’s ambassador to Ottawa, said he couldn’t confirm the authenticity of the documents, but said it was standard practice for an embassy to compile information about those it saw as security concerns. “Any embassy would focus on the threats targeting their countries. That’s what every embassy does,” he said in an interview.

In all, 26 people, including family members of the suspects living in both Canada and Turkey, are named in the case files. There are likely others in Canada under surveillance beyond the 26 – Mr. Uras said that Canada had “a big open door” to followers of the Gülen movement, and that “thousands” of people had moved from Turkey to Canada after the failed coup. “They are continuing their political activity here. … They have their front operations, their NGOs.”

The Globe and Mail spoke with more than half of those named as suspects in the Ankara court documents. Most were not surprised to hear they were on a Turkish government blacklist, even as they denied any involvement with terrorism. Several said they had already assumed, before hearing of the court records, that it was not safe for them to return to Turkey while Mr. Erdoğan was president.

“I cannot go back to Turkey, I know that. I don’t feel safe. Several of my friends went to Turkey and got arrested, so I cannot take that risk,” said Hasan Yılmaz, publisher of CanadaTurk, a Toronto-based monthly newspaper. The court documents say that Mr. Yılmaz and his publication “operated under the control of the [Gülen] organization in Canada,” which he says is untrue.

“Whoever opposes this government, I think, is on a list,” Mr. Yılmaz said.

Mr. Yılmaz said he closed his newspaper in 2016 because he began receiving death threats in the wake of the failed coup. Mr. Yılmaz started publishing CanadaTurk again this year, but said he now avoids politics.

Part of the information compiled against four of the suspects notes they downloaded ByLock, a messaging application popular among supporters of Mr. Gülen.

“I’m surprised, but not surprised at the same time. I knew the intelligence apparatus of the state was following people, but I’m surprised to be on their list,” said one of those named as a suspect, a Toronto resident who formerly worked at the Intercultural Dialogue Institute, a non-governmental organization that was founded in 2010 by supporters of Mr. Gülen. The file says the man was “one of the prominent executives members of the [Gülen] organization in Canada.”

The man said he had indeed downloaded ByLock, but denied he was an important member of Mr. Gülen’s movement. “None of the people on the list [in the court documents] are decision-makers.”

The Globe and Mail is not naming any of those identified as suspects in Turkey, unless they agreed otherwise, since they are not accused of doing anything that would violate Canadian law. Several said they feared they would be stigmatized if they were publicly named as terrorism suspects.

The Intercultural Dialogue Institute says on its website that it was “founded by Turkish Canadians inspired by the teachings and example of Fethullah Gülen.” The group says it “aims to facilitate dialogue on a whole range of social issues, regardless of any particular faith or religion. It stands for democracy, human rights, the non-instrumentalization of religion in politics, equality and freedom of speech.”

The Turkish government sees Mr. Gülen very differently. The 79-year-old Islamic scholar was a close ally of Mr. Erdoğan until Mr. Gülen accused Mr. Erdoğan’s government of corruption in 2013. Turkey considers Mr. Gülen to be the architect of the failed 2016 coup d’état, and lists the Gülen movement as a terrorist group, making it illegal to support Mr. Gülen.

Pakistan, Somalia, Kyrgyzstan and Azerbaijan are the only other countries that consider the Gülen movement (which the Turkish government calls FETO) to be a terrorist organization.

Mr. Yılmaz, the publisher of CanadaTurk, said the country’s political climate changed in 2013. “All the Turkish officials and diplomats, pre-2013, we used to go to dinner and play soccer together on the weekends. Then the next day [after the corruption allegations], they started calling us terrorists.”

Mr. Gülen’s supporters say the coup attempt was staged by the government to justify the crackdown that followed. He is living in exile in the United States. Mr. Erdoğan has repeatedly asked U.S. President Donald Trump to extradite his nemesis to face trial in Turkey.

Mr. Uras, the ambassador, said his government was frustrated that friendly governments didn’t share Turkey’s view of the Gülen movement. “These people carried out a coup. They killed 253 of our citizens, and wounded thousands,” he said.

Mr. Uras compared his embassy’s monitoring of Gülenists to the way the Canadian embassy in Ankara pays attention to Canadians who travelled to Syria and Iraq to join the Islamic State.

(Among those arrested in the postcoup crackdown on Mr. Gülen’s supporters was Tuncay Babalı, Mr. Uras’s predecessor as Turkish ambassador to Ottawa.)

In a statement, the Intercultural Dialogue Institute said the court documents showed “the Erdoğan government has not stopped at its own borders.” The group thanked the Canadian government for “standing up for human rights, its adherence to the rule of law, and its ability to stand up to Erdoğan.”

Canada has accepted nearly 5,000 refugees from Turkey since the 2016 coup, the highest number of any country over that period. While not all are members of the Gülen movement, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada appeared to routinely accept that asylum seekers would face persecution if they returned to Turkey.

The influx of political refugees has come surveillance. In its most recent annual report, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service expressed concern about foreign powers who “have attempted to covertly monitor and intimidate Canadian communities in order to fulfill their own strategic and economic objectives.”

But in response to questions from The Globe and Mail, CSIS would not say whether this criticism extends to Turkey. The federal intelligence service does not “comment on the specifics of our investigations, operational interests or reporting, methodologies, activities or interactions with foreign partners,” said John Townsend, a CSIS spokesman.

The Ankara court documents were initially obtained by Abdullah Bozkurt, a Turkish journalist who has himself been in exile since the 2016 coup. Mr. Bozkurt shared the files with The Globe.

Mr. Bozkurt‘s former employer, the Today’s Zaman newspaper, is considered to have been close to the Gülen movement, and the paper was forced to close after the coup attempt. Naming people as Gülenists “is just a pretext for the Turkish government to label its critics,” Mr. Bozkurt said in an interview. “This is how the Turkish government abuses the charge of terrorism.”

The consequences for those named in the court documents are potentially serious. “The ramifications are quite alarming. We have seen so many different cases where people have been prosecuted based on these profiling documents – whether the information in them is true or not,” Mr. Bozkurt said from Sweden, where he now runs a think tank called Nordic Monitor.

“Since my name is out there, I have no hope of going back to Turkey to see my aging parents,” said an academic in Southwestern Ontario. He was named in the terrorism investigation because, according to the documents, he “shares current posts in favor of [the Gülen movement] on social media sites.”

The man said he had ceased any affiliation with the Gülen movement years ago, and now considered himself a critic of both Mr. Gülen and Mr. Erdoğan. “All the information [in the court file] is false. It’s just wrong.”

The blacklist also names several Southern Ontario-based real estate agents who are originally from Turkey. The documents contend that their continuing involvement in the buying and selling of homes is a potential indicator of their involvement in financing “terrorist” activity.

When the real estate agents were contacted by The Globe and Mail about these allegations, their reactions ran from shock and indignation to resignation.

Several said they were doing business partly to accommodate waves of Turks seeking a safe haven from political persecution.

“I’m a real estate agent right now and I represent the Gülen movement also,” one realtor said. “This is an honour for me because it is not a terrorist organization.”

He explained that he had visited the exiled cleric in the United States several times, and said he had helped run some affiliated schools in Canada.

“What kind of terrorist groups support education? What terrorist groups open universities?” the realtor said. He argued that Mr. Gülen stands for peace and pluralism and education, whereas “the Erdoğan regime closed down everything. He closed more than 20 universities and 1,000 schools and dormitories.”

Another realtor said he used to be involved with the Turkish Canadian Chamber of Commerce, one of several Canadian-based organizations that the Turkish blacklist names as fronts for the Gülen movement. The realtor said that his wife had already made him quit the business association and other Gülen-linked groups, for fear of fallout from Ankara.

He added that he already knew that he must be under some sort of cloud because Turkish diplomats used to invite him to their business functions – but then suddenly stopped doing so. “Right now, I don’t want to be any member of any groups because you don’t know what’s going to happen. They are making you into terrorists and stuff,” he said.

Mr. Bozkurt, who has been involved in a number of scoops that embarrassed the Turkish government (including revelations about Turkey’s intelligence services funnelling weapons to jihadi groups in Syria, as well as a story about the monitoring of Turkish Americans in the United States), has been accused by the Daily Sabah, a pro-Erdoğan newspaper, of circulating “fake information and forged documents” with the aim of turning foreign governments against Mr. Erdoğan.

“My answer is, if you don’t trust what I write, here are the documents,” Mr. Bozkurt said. “They know very well it’s true, because they have the same documents themselves.”

Those named as Gülenists are treated often harshly by Turkey’s judicial system. “In Turkey, there is no law. There is no democracy. There is a kind of tribal law. If they don’t find you, they arrest your wife. Or your kid. Whatever they find at all. And they say [to the person they arrested], ‘If your husband comes, we will let you go,‘ ” said Davud Hancı, a Canadian citizen who was jailed for three years in his native Turkey on allegations that had played a role in the 2016 coup. Mr. Hancı, who was released late last year, is not named in the documents obtained by The Globe.

“I just see it as a power struggle within the state, between two groups of people. The elephants had a struggle, and the grass was the victim,” added the former executive at the Intercultural Dialogue Institute who was named in the Ankara court documents. “I have found myself in the middle of a dirty, dirty power struggle.”