Mustafa Erkan Acar (45), a Turkish journalist with 22 years of experience, has been deprived of his freedom for 557 days as of Feb. 2, 2018. Acar, who served for many years in the now-closed Zaman and Bugün newspapers, was arrested after the controversial military coup attempt on July 15, 2016. He has been prosecuted with 15 years of imprisonment for alleged “membership in an armed terrorist organisation.”

Erkan Acar had criticised the appointment of trustees to Bugün daily by the government by saying that “My newspaper turned into prison,” the newspaper’s headquarters was filled with policemen. But later he has been imprisoned in Silivri Prison for 18 months.

Erkan Acar, who has two children, was born in Bursa in 1973. In 1995, he graduated from the Department of Journalism of Faculty of Communication at Ege University. In the same year, he started to work as a reporter in the Zaman daily’s regional office in İzmir province. He was appointed to İstanbul in 1999. He served in the newspaper’s İstanbul newsroom. He had signed numerous exclusive news files during his 9 years as investigative reported in Zaman’s headquarters. So, he was prompted to the position of the news coordinator of the daily in 2009.

He was transferred to Bugün daily as the news director of the daily in 2013. He fulfilled this task until the newspaper was seized forcefully by the Turkish government in October 2015. Then he continued his professional life as a news director in a newly founded newspaper Özgür Düşünce (Free Thought). However, following the controversial coup attempt on July 15, 2016 this newspaper was also closed by a government decree under the rule of law declared in the aftermath of the coup bid.

Acar, known with his earth-chattering exclusive news stories and investigative journalism, had become the first journalist in Turkish media who wrote over the mobilization of the news neo-nationalist current in Turkey at the beginning of 2000s. He had focused especially on the alliance between the nationalist and neo-nationalists. He drew attention to this new pro-Russian ultra-nationalist ideological formation, which is anti-EU and anti-NATO. He was also one of the journalists in Turkish media who had pointed out Ergenekon, a deep state structure, which was revealed by the legal investigations started in 2008. Therefore, he was one of the journalists who have been targeted by these well organised ideological deep state circles.

The indictment about these jailed journalists was released at the beginning of March 2017, namely 7 months after their imprisonments. Prosecutor Murat Çağlak had generally included their tweets as evidence for other journalists being tried in the same case. But, Çağlak could not do the same thing for Acar. Because it is stated that Erkan Acar closed his twitter account on the evening of July 15, 2016. But even this was shown in the indictment as a crime evidence: “The suspect, Mustafa Erkan Acar, has closed his twitter account as it was made by the majority of the members of the organization after the coup attempt on July 15.” Therefore, the prosecutor, who is deprived of the luxury of generating a crime by scanning Acar’s tweets backwards, has directed him such an accusation instead.

In addition, a person named Mehmet Alakuş, by mentioning account of the General Directorate of Security on Twitter, wrote that “@acarerkan closed his account. He is going to flee abroad, catch him.” It has been argued that Acar was arrested based on this trivial denunciation.

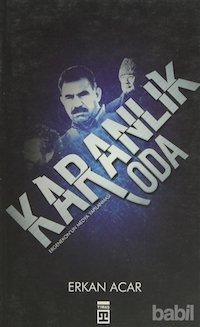

Journalist Acar’s published books have also been included by Prosecutor Çağlak into the indictment. But there is no solid accusation. Only pro-government online smear site Medya Gündem’s comments about his books were quoted as evidence. The prosecutor also mistakenly named the site as “Genel Gündem” in the indictment. In the mentioned article, it is stated that Erkan Acar published some telephone conversations among the names close to Doğu Perinçek, the chairman of the net-nationalist Labor Party (now the Homeland Party), whose telephones allegedly tapped illegally by the police department. Prosecutor Çağlak has repeated the same allegations after placing the same comment in the indictment.

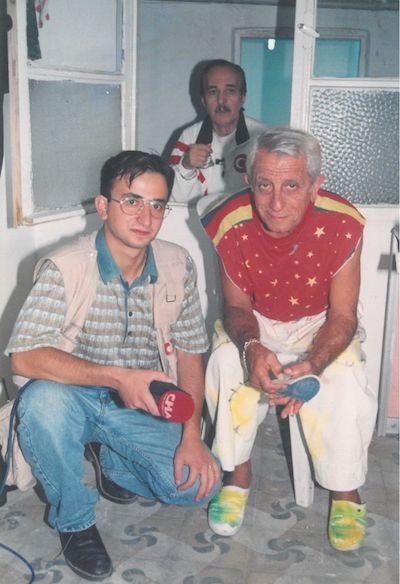

Acar had given an interview to an online news website called ‘Emir Haber’ on November 1, 2015. In this interview, Acar had criticized the government’s decision to seize İpek Media Group. He was asked questions such as “Are you working for a newspaper which seems to be a prison surrounded by the police barricades and ‘TOMA’s (anti-riot armored vehicles) or, Are you a convict in a semi-open jail? Is this a prison interview? What happened in ‘Bugün’ daily?

Acar had replied the questions such as “My newspaper building has just turned into a prison. We can enter the building after a matching/cross identity check. Two police officers stand guard in each floor (of the newspaper building). Editorial staff meetings are held with the presence of the (government appointed) trustees and the police. Furthermore, there are lawlessness in the seizure (…) on Friday, October 30, 2015. When I arrived at the office, police met me at the gate with a list of names saying I was fired. I had my personal belonging inside, but they did not let me in. (…) They are committing a crime indeed (…) We are paying the price for writing, revealing the truth and raising our voice without hesitation. (…) We were freely doing our job (in this newspaper). Believe me, I did not expect such a police raid. We expected that the police would come and only search in the newspaper. We did not anticipate the police from Organized Crimes Bureau would raid and numerous people (newspaper staff) would be dragged on the ground. We were treated like the members of a terror organization.”

Public Prosecutor Çağlak included this interview in the indictment by handling Acar’s criticism against the decision of seizure as a criminal act.

Acar and other jailed journalists, who have been tried in the same case, could eventually stand before a judge on March 27, 2017 for the first time after 8 months of imprisonment with this indictment. In his defence, Acar refused the charges and said that “I have been a journalist for 22 years. I have written two books. I have not done anything else but journalism. ‘Özgür Düşünce’ newspaper is called a media organ of a terror organization in the indictment. I have never felt that because it was a legal institution. As a matter of fact, several months before the coup attempt our current Prime Minister Binali Yıldırım invited our Ankara correspondents to breakfast.”

Following 5 days of the trial, 21 out of 26 jailed journalists were released. One of them was Erkan Acar. But none of these 21 journalists could get out of the prison due to the social media lynching and government’s direct intervention to judicial process.

Prosecutor Göksel Turan had demanded the release of 13 journalists, but judge İbrahim Lorasdağı had released 21 journalists after the hearing. As soon as the court decision was announced, a bitter social media lynching campaign was launched. Pro-AKP journalists had objected to the decision of release and made a call for the government not to set these journalists free. These pro-government journalists had called the Justice Ministry to intervene the judicial process and started tossing threats on social media.

There were news on the social media that the Justice Ministry intervened before the releases were implemented. The judges, who were affected by the social pressure, could not release none of these 21 journalists. Then the Council of judges and Prosecutors (HSK) dismissed the court delegation. İstanbul 25th High Criminal Court president İbrahim Lorasdağı, court panel members judge Barış Cömert and Necla Yeşilyurt Gülbiçim and hearing prosecutor Göksel Turan were temporarily removed from their duties.

Second hearing of the journalists, including Erkan Acar, were held on April 27, 2017. And the court ruled that his and other journalists’ detentions to continue. On July 7, 2017, he stood third time before the judge and again his detention continued. Lastly, on December 4, 2017 Acar was not released after the fifth hearing of the case. The sixth hearing was scheduled for the February 6, 2018.

Turkey is the biggest jailer of journalists in the world. The most recent figures documented by the SCF has showed that 245 journalists and media workers are in jails as of January 24, 2018, most in pre-trial detention languishing in notorious Turkish prisons without even a conviction. Of those in Turkish prisons, 218 are arrested pending trial, only 27 journalists remain convicted and serving time in Turkish prisons. An outstanding detention warrants remain for 140 journalists who live in exile or remain at large in Turkey.

Detaining tens of thousands of people over alleged links to the Gülen movement, the government also closed down more than 180 media outlets after the controversial coup attempt.