Family and Social Services Minister Mahinur Özdemir Göktaş touted Turkey’s disability rights policies at a global summit in Berlin, but disabled citizens say the government’s promises remain unfulfilled, the Bianet news website reported.

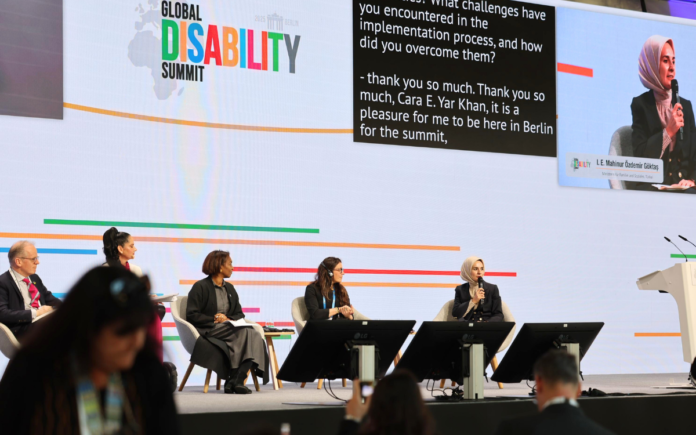

The minister spoke at the Global Disability Summit, co-hosted April 2-3 by Germany, Jordan and the International Disability Alliance, where more than 4,500 participants from around 100 countries gathered. While Göktaş highlighted Turkey’s legal frameworks and accessibility strategies, disabled people back home criticized what they called a growing gap between rhetoric and reality. Their reactions were gathered in a series of interviews conducted by Bianet.

“No one from our community even attended the summit,” one visually impaired person said. “She’s speaking for us, but not with us.”

Göktaş described accessibility as “foundational” to disability rights and cited Turkey’s 2005 Disability Act, the 2010 Accessibility Strategy and more recent measures such as the Accessibility Year initiative and certification programs. But disabled citizens interviewed said those policies have yet to produce meaningful changes in everyday life.

“The law may exist, but it’s ignored,” said a wheelchair user in Istanbul. “Even buses with accessibility features often don’t work. There’s no accountability,” another interviewee added.

Some pointed to chronic delays in implementing accessibility regulations. “Every few years they extend the deadline again. It’s like the law only exists to be postponed,” one person said.

Others shared examples from their daily lives: persistent difficulty accessing healthcare, a shortage of trained support personnel in schools and physical infrastructure that often obstructs rather than enables.

One individual with autism said even special education institutions fall short of meeting basic accessibility needs. “The ramps [for wheelchair users] are either too steep or lead to locked doors,” they said.

Interviewees also challenged Göktaş’s portrayal of Turkey as a model country for accessibility. Many described the national approach as symbolic rather than structural. “They speak in big words, but there’s nothing behind them,” said one interview participant. “On paper, Turkey looks great, in practice, it’s one of the least accessible places I’ve lived.”

Five years after Turkey declared 2020 the “Year of Accessibility,” critics say little has changed. “The only progress is in award ceremonies, not our lives,” one interviewee said.

People with disabilities in Turkey continue to face significant barriers in education, employment, public infrastructure and access to services. While the country has ratified international agreements such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, critics say enforcement remains weak, data on inclusion is limited and policymaking often lacks meaningful consultation with disabled individuals. Rights groups have long urged the government to move beyond symbolic initiatives and adopt systemic reforms rooted in participation, accountability and universal design.