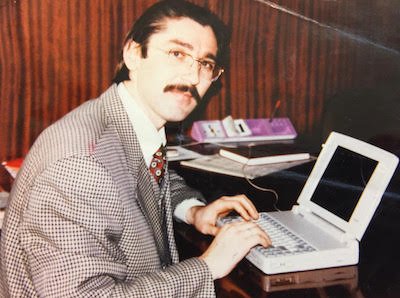

Mustafa Ünal, a veteran journalist and Ankara bureau-chief for shuttered Zaman daily has been behind bars for 508 days for published articles and Tweet messages that are deemed critical of the Turkish government.

The public prosecutor asks for three aggravated life sentences and additional 15-year jail sentence for Ünal and cites nine op-ed articles published in the newspaper as evidence of crime for terrorism. None of the columns written by 50-year old journalist in the last fifteen years he had been writing for Zaman were subject to a legal complaint and he has never been sued by the government until the controversial coup attempt on July 15, 2016.

When he got detained, the lawyer appointed by the Bar Association told Ünal that he would be unlikely arrested given the line of questioning at the police station. He was wrong. The prosecutor directly referred Ünal to the court for an arraignment hearing with a demand of pre-trial detention. He was formally arrested and sent to notorious Silivri Prison in İstanbul.

Ünal appeared before the judges after spending 420 days in pre-trial detention. He did not know how to defend himself as the indictment only listed his nine articles with titles without explaining what in those articles actually constituted a crime.

In a bizarre case, the public prosecutor wrote in the indictment that: “Despite they apparently do not constitute any crime, they include expressions that violate the rights of the state institutions and state officials by abusing the freedom of press and expression.”

There is actually no expression in Turkish penal code as rights of the state institutions and state officials. It begs a further question how he is facing lifetime sentence when the evidence listed in the indictment is admitted by the prosecutor as having no bearing as criminal act.

Instead of listing offences along with the evidence with respect to each and every individual suspect in the case where Ünal and other journalists were accused of serious charges of terrorism and coup plotting, the prosecutor simply put all critical columnists and media workers into the same basket and asked for collective punishment in the indictment.

In his defence, Ünal recalled the prosecutor’s statement in the indictment and asked the panel of judges if they had ever heard the violation of rights of the state officials and institutions in the penal code.

“I did not hear. I asked that to many legal experts, they did not either,” Ünal replied.

“If the intent is ‘defamation,’ its penalty is not three life sentences,” Ünal told, stressing that no defamation case has ever been filed against him in his lifetime of journalism career.

Most of the op-ed pieces cited in the indictment as evidence of the crime is about the country’s largest ever corruption probes that incriminated President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then-Turkish Prime Minister, his family members, cabinet ministers, and his business and political associates. The probes were made public in December 2013.

Regarding his columns on graft probe, Ünal told judges “Any claim about a politician is news worthy. A journalist cannot turn a blind eye on these allegations.”

The journalist also recalled that former prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu urged his ministers to stand trial to come up clean and referred opposition leaders’ supportive remarks on corruption investigations. Ünal asked why the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) did not nominate ministers –who were accused of taking bribes in exchange for government favours – again for a seat in Parliamentary elections.

Ünal was detained in Ankara on July 27, 2016. After news began circulating that his name was among the journalists for whom the government issued detention warrants, he waited the police for 12 hours at his home. Ünal asked the panel if a person who waited 12 hours at his home to be detained by the police knowing that a detention warrant issued for him could be a terrorist? He rejected the court ruling that stated he poses a flight risk and therefore must be jailed pending trial.

In the indictment, Ünal is bizarrely accused of interviewing Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, head of Turkey’s main opposition Republican Peoples’ Party (CHP). Kılıçdaroğlu met Ankara representatives of various media outlets on December 25, 2015 for a year-end meeting and upon a question, he said to participants that “His party was the one that criticized the Gülen movement at most. However they [CHP] would stand by the oppressed if [the government] was to exterminate [the Gülen movement] since they dissented from the government, asked who they would defend other than the oppressed?” Ünal is charged with making terror propaganda for carrying the CHP leader’s statement in his newspaper despite many other newspapers and TV channels did so as well.

During the second hearing in the trial on December 8, 2017, he asked “How can I overthrow the government and stage a coup and amend the constitution by writing columns?” He did not get any response. His next trial will be held on April 5, 2018.

Ünal, a graduate of a religious high school or İmam Hatip Lisesi, has struck close ties with many politicians in Ankara, especially among those who come from Islamist backgrounds. Abdullah Gül (former prime minister and president) and Bülent Arınç, former speaker of the parliament, were frequent visitors of Ünal at his home and office in 1990s when they were in the opposition.

Father of two, Ünal is known for his love for poetry and literature.

Turkey is the biggest jailer of journalists in the world. The most recent figures documented by the SCF has showed that 248 journalists and media workers are in jails as of December 19, 2017, most in pre-trial detention languishing in notorious Turkish prisons without even a conviction. Of those in Turkish prisons, 221 are arrested pending trial, only 27 journalists remain convicted and serving time in Turkish prisons. An outstanding detention warrants remain for 139 journalists who live in exile or remain at large in Turkey.

Detaining tens of thousands of people over alleged links to the Gülen movement, the government also closed down more than 180 media outlets after the controversial coup attempt.

Turkey survived a controversial military coup attempt on July 15, 2016 that killed 249 people. Immediately after the putsch, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government along with President Erdoğan pinned the blame on the Gülen movement.

Gülen, who inspired the movement, strongly denied having any role in the failed coup and called for an international investigation into it, but President Erdoğan — calling the coup attempt “a gift from God” — and the government initiated a widespread purge aimed at cleansing sympathizers of the movement from within state institutions, dehumanizing its popular figures and putting them in custody.

Turkey has suspended or dismissed more than 150,000 judges, teachers, police and civil servants since July 15. Turkey’s Interior Minister announced on December 12, 2017 that 55,665 people have been arrested. Previously, on December 13, 2017, The Justice Ministry announced that 169,013 people have been the subject of legal proceedings on coup charges since the failed coup.

[…] “Mustafa Ünal, a journalist with 28 years of experience, was Zaman’s Ankara Bureau Chief when the newspaper was confiscated on March 4, 2016. He was a columnist for 20 years and accompanied the Turkish President and the Prime minister at their many domestic and foreign trips. Until he was arrested, he had no legal case at courts for a story or an article he had penned. In the wake of the coup attempt of July 15, 2016 he was arrested on July 30, 2016. He is still in prison. In his indictment, the articles he had written are shown as evidence for being a member of a terrorist organization. […]

[…] Mustafa Ünal (50), a veteran journalist and former Ankara bureau chief for the shuttered Zaman daily, said in a letter from İstanbul’s notorious Silivri Prison, “There is no legal justification for ruling for the continuation of my imprisonment.” […]

[…] Mustafa Ünal (50), a jailed veteran journalist and former Ankara bureau chief for the shuttered Zaman daily, has urged the judges in his trial to comply with the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and Turkey’s Constitutional Court (AYM), saying, “My screams for justice have faded away in a bottomless pit.” […]