Amnesty International said, in a report released Thursday, the fact that prisoners of conscience have been left to languish in appalling conditions despite a widely publicized release program shows that the Turkish government fears criticism more than the pandemic.

The report, titled “Daring to Stand up for Human Rights in a Pandemic,” documents attacks on human rights defenders during the pandemic and states that governments which were lauded for releasing prisoners in response to COVID-19 outbreaks have excluded human rights defenders from the measures and continue to make new arrests of activists, journalists and critics.

“COVID-19 has been an added punishment for human rights defenders who are unjustly imprisoned, and has also been used as a pretext for further harassment, prosecution and even killings,” said Lisa Maracani, Amnesty International’s researcher on Human Rights Defenders.

In Turkey decongestion measures have explicitly excluded those who are held in pre-trial detention, and those who are on remand for or have been convicted of offenses under Turkey’s overly broad anti-terrorism laws. They include political and human rights activists, journalists, academics and others who have spoken out against the government.

The Turkish parliament passed a release bill in mid-April to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in the country’s overcrowded prisons. Providing the possibility of early parole or house arrest to inmates, the law explicitly excluded those who are held in pre-trial detention and tens of thousands of political prisoners such as politicians, journalists, lawyers, academics and human rights defenders convicted under the country’s controversial and broadly interpreted counterterrorism laws. The government turned a deaf ear to calls from international organizations, NGOs and rights groups to include political prisoners within the scope of the release law.

According to Maracani, the exclusion of human rights defenders from release measures in fact “underscores the political nature of their imprisonment. In Turkey, for example, journalists, lawyers, activists and opposition politicians held in pre-trial detention on baseless charges remain behind bars despite government measures that have seen over 100,000 people released since April.” This shows that “the Turkish government still fears criticism more than the pandemic,” Maracani said.

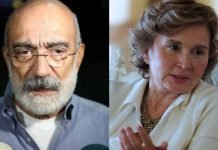

Amnesty’s report mentions high-profile journalist and novelist Ahmet Altan, Kurdish politicians Selahattin Demirtaş and Gülten Kışanak, and businessman and civil society activist Osman Kavala as examples of those who have been detained since the wave of repression started in 2015. The report also underlined that many more academics, human rights defenders and journalists have been in prison on terrorism-related charges, which are often used to target those who dare to speak out and others perceived to be opponents of the government.

The report ends with a series of recommendations to states worldwide, including calls on states “to immediately and unconditionally release all those who remain in detention solely for the peaceful defense of human rights; stop discriminating against, criminalizing, intimidating and endangering human rights defenders who speak up and contribute to the efforts to protect public health and tackle the pandemic; and ensure that any measure restricting the right to defend human rights is strictly necessary and proportionate for the protection of the public health or other relevant legitimate purpose under international human rights law.”