Turkish banks continue to deny basic services to civil servants summarily fired by the Turkish government in the aftermath of an abortive putsch in July 2016.

In a tweet on Wednesday, Levent Mazılıgüney, a dismissed public servant, said his credit card application to VakıfBank was denied despite the fact that he is a registered lawyer and his credit score is 1,860 out of 1,900.

Bir iktisatçı olarak sorayım. Kredi notu 1860/1900 olan bir müşteriye kredi kartı vermemek hangi risk hesabı hangi iktisadi ilkeyle açıklanır @VakifBank? KHK'lılara sivil ölümden başka yol tanımıyor musunuz? İhtiyacım olduğundan değil, bu rezilliğe son vermek için uğraşacağım. https://t.co/Wdab1mtNHQ pic.twitter.com/2rGQX3Wr1w

— Levent MAZILIGÜNEY (@Leventism) November 4, 2020

Following the coup attempt in July 2016, the Turkish government declared a state of emergency and launched a massive crackdown under the pretext of an anti-coup fight. Over 150,000 civil servants were removed from their jobs for alleged membership in or relationships with “terrorist organizations.”

The purge mainly targeted people who were allegedly affiliated with the Gülen movement, a faith-based group inspired by Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen, but included other people from a wide variety of backgrounds as well. The Turkish government accuses the movement of masterminding the failed coup. Gülen and the movement denies involvement in the coup or any terrorist activity.

Former public servants were not only fired from their jobs; they were also banned from working again in the public sector and getting a passport. The government also made it difficult for them to work formally in the private sector. Notes were put on the social security database about dismissed public servants to deter potential employers.

Speaking to the Ahval news website in January, Mazılıgüney said he was financially paralyzed immediately after he was fired. “I was dismissed by a government decree on Saturday. In April 2017,” he said. “By Monday, all my credit cards were cancelled. My bank accounts were frozen.”

In a similar case, Nazmiye Aydın, a dismissed teacher, received a renewal of her credit card from the bank in 2019 but was unable to use it. When she inquired about it, she was told by a bank employee that the restriction on the card would not be lifted until she was acquitted by a court.

She did not receive an official explanation from the bank at the time. After a brief correspondence, Halkbank in February replied with an official explanation indicating that Aydın’s card was canceled due to her dismissal.

Turkey’s state-run Halkbank admitted that it canceled a credit card last year because the owner of the card was a dismissed civil servant.

In another well-known case, Garanti BBVA, an affiliate of Spanish Bank BBVA, refused to open a bank account for a dismissed public servant. The bank had to reverse its position after the pro-opposition media covered the incident extensively and agreed to open a restricted checking account. The account holder could only use his account for withdrawing his salary. Other banking transactions such as money transfers were still prohibited.

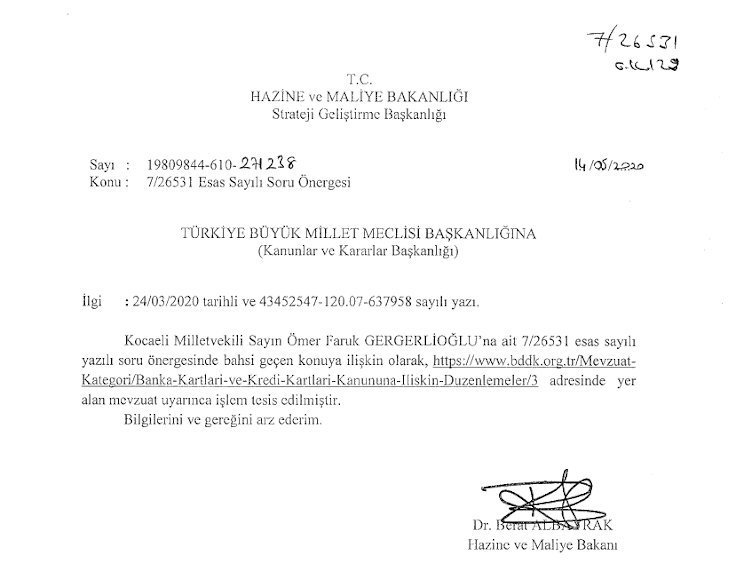

In response to parliamentary questions posed by Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, a pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) deputy and a rights activist, on discrimination by banks against public servants fired by the Turkish government, Treasury and Finance Minister Berat Albayrak only provided a website link to Turkish banking regulation according to a report by the Gazete Duvar news website.

Gergerlioğlu had asked why former public servants’ bank accounts were blocked and why banks refuse to open new accounts or issue credit cards to them.

Turkish insurance companies also discriminated against the purged public servants in the recent past. In one case Doğa Sigorta refused to cover damages to an automobile owned by former civil servant H.B. The insurance company was supposed to pay damages in the amount of TL 20,000 to the family according to their policy. Yet, they refused to make the payment, saying the government had instructed them in a directive not to make payments to dismissed public servants.