Turkey has fallen dramatically in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) 2023 World Press Freedom Index, slipping 16 places and ranking 165th among 180 countries, not far from North Korea, which occupies the bottom of the list, Turkish Minute reported.

The 21st edition of the World Press Freedom Index, compiled annually by RSF, was published on Wednesday on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day, marked on May 3.

Although Turkey had a relatively better ranking in the same index in 2022, in 149th place among 180 countries, freedom of the press in the country has significantly deteriorated, going from “problematic” to “very bad” as the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has increased its crackdown on journalists in the run-up to presidential and parliamentary elections on May 14.

In RSF’s first press freedom index published in 2002, the year when the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power, Turkey had a ranking of 100th among 139 countries, dropping to 151st in 2016, 155th in 2017, 157th in 2018 and 2019, 154th in 2020 and 153rd in 2021.

RSF said Erdoğan’s “hyper-presidency” has stepped up its attacks on journalists in a bid to deflect attention from the country’s economic and democratic decline and to shore up its political base.

Through a referendum in April 2017 Turkey switched from a parliamentary system of governance to an executive presidential system that granted Erdoğan and his government sweeping powers and was criticized for removing constitutional checks and balances, thus leading to a further weakening of Turkish democracy.

“However, tactics such as near systematic censorship on the internet, frivolous lawsuits against critical media outlets or the misuse of the judicial system have, until now, enabled Erdoğan to restore his popularity rating, while he continues to be embroiled in a major case of corruption and political clientelism,” RSF says in the index.

Political analysts say Erdoğan is facing the most challenging election of his career amid the political and social woes in the country, which was hit by two powerful earthquakes in February that claimed more than 50,000 lives and brought much criticism to the government due to its poor and ineffective response to the disaster.

Opinion surveys show Erdoğan neck-and-neck with his main rival Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the joint presidential candidate of an opposition alliance, or losing to him.

According to the Media and Law Studies Association, there are at least 66 imprisoned journalists and media employees in Turkey, 32 of whom have been arrested in the past 10 months alone.

Since last week, Turkey has seen the arrest of nine journalists, who for the most part work for pro-Kurdish media outlets, on terrorism-related charges. According to the Mezopotamya news agency, 34 journalists who work for pro-Kurdish media outlets have been arrested over the past 11 months.

Kurdish journalists or those working for pro-Kurdish media outlets are the subject of frequent legal harassment and prosecution in Turkey as they are accused of links to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) for covering issues related to the PKK or the problems faced by the country’s Kurds.

The PKK, which has been waging a bloody campaign in the country’s southeast since 1984, is listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey and much of the international community.

RSF said with 90 percent of the national media now under government control, the public has turned, during the past five years, to critical or independent media outlets of various political persuasions to learn about the impact of the economic and political crisis on the country, which include local TV channels such as Fox TV, Halk TV, Tele1 and Sözcü, and international news websites such as BBC Turkish, VOA Turkish and Deutsche Welle Turkish.

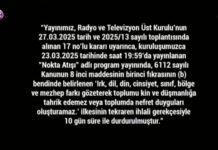

Local TV channels face frequent broadcasting bans and fines imposed by the country’s media watchdog, the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), for broadcasting content critical of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government. International news websites such as VOA Turkish and Deutsche Welle Turkish also receive their share of punitive actions as they were banned in June 2022 for failing to apply for online broadcasting licenses, a RTÜK demand that they said was tantamount to censorship.

Legal framework

In its report RSF also said discriminatory practices against critical journalists and media outlets, such as stripping them of press passes, are commonplace, while judges who do the government’s bidding are trying to limit democratic debate by censoring online articles tackling corruption and similarly sensitive topics.

“This makes it hard to publish quality reporting. Some journalists have nonetheless tried to remain faithful to their mission to report the news with complete independence, and they are demanding recognition of a ‘media ombudsman’,” said RSF.

Sociocultural context

According to RSF, journalists who criticize or question well-known religious figures are sometimes the targets of lawsuits accusing them of “insult.”

It is common for journalists as well as ordinary citizens in Turkey to face charges of insult due to their criticism of Erdoğan or members of his government.

“References to domestic violence or various forms of abuse, especially when made by women journalists, can give rise to social media hate campaigns.”

Safety

With regards to the safety of journalists, RSF said the spiral of violence targeting journalists critical of the ruling AKP-Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) alliance has intensified since the 2019 local elections.

“As the 2023 elections approach, ultra-nationalist groups, spurred on by anti-media political rhetoric, are taking to the streets to attack reporters, columnists, commentators and citizen-journalists who cover politics and discuss the economic crisis.”

In the RSF index, Norway is ranked first for the seventh year running, but a non-Nordic country — Ireland — is ranked second, ahead of Denmark (down 1 place at 3rd).

There are changes at the bottom of the index as well. The last three places are occupied solely by Asian countries: Vietnam (178th), which has almost completed its hunt of independent reporters and commentators; China (down 4 at 179th), the world’s biggest jailer of journalists and one of the biggest exporters of propaganda content; and, in no great surprise, North Korea (180th).