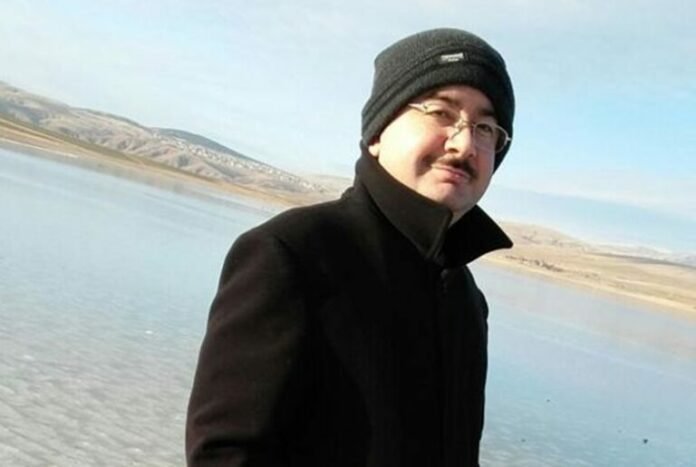

Yasin Akaslan, 41, a bookstore manager who was arrested in March 2020 for alleged affiliation with the Gülen movement and sent to central Turkey’s Kırıkkale Prison despite suffering from leukemia, has developed additional health problems in prison.

According to the Bold Medya news web site, Akaslan’s sister Kevser Sinan said in a letter that he had not been able to take his prescribed medication in prison and was later given a different medication. She claimed that after a while he felt worse and that bruises appeared on his body.

Sinan, who was also arrested on similar charges and sent to the women’s ward of the same prison, added that it was difficult to recover once a person gets sick in prison, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. “If you go to the hospital, you need to stay in a quarantine cell for up to 40 days,” she said. “The conditions of the quarantine cells are difficult to endure.”

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been targeting followers of the Gülen movement, a faith-based group inspired by Turkish cleric Fethullah Gülen, since the corruption investigations of December 17-25, 2013, which implicated then-Prime Minister Erdoğan, his family members and his inner circle.

Dismissing the investigations as a Gülenist coup and conspiracy against his government, Erdoğan designated the movement as a terrorist organization and began to target its members.

Dismissing the investigations as a Gülenist coup and conspiracy against his government, Erdoğan designated the movement as a terrorist organization and began to target its members. He locked up tens of thousands including many prosecutors, judges and police officers involved in the investigations as well as journalists who reported on them.

Erdoğan intensified the crackdown on the movement following a coup attempt on July 15, 2016 that he accused Gülen of masterminding. Gülen and the movement strongly deny involvement in the abortive putsch or any terrorist activity.

According to a statement from Turkish Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu on November 26, a total of 292,000 people have been detained while 96,000 others have been jailed due to alleged links to the Gülen movement since the failed coup. The minister said there are currently 25,655 people in Turkey’s prisons who were jailed due to links to the movement.

The violation of prison inmates’ basic rights in Turkey is one of the topics raised frequently by activists and human rights defenders. Earlier this year two prisoners, journalist Mevlüt Öztaş and TV director Fatih Terzioğlu, succumbed to cancer, which they developed in prison and for which they could not get proper treatment. Both were refused the postponement of their sentences they were entitled to and were belatedly released despite medical reports attesting to the fact that they were unfit to remain in prison.

Pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) deputy and rights activist Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu said in August that imprisoning sick patients was as an act of murder committed by authorities who refused to release them.

“They refuse to release the prisoners until it reaches the point of no return. They only release the prisoners when they realize they will die soon, not wanting them to die in prison,” he said.

Gergerlioğlu claimed that prisoners do not have proper access to healthcare facilities such as an infirmary or a hospital. “They have trouble getting sent to a prison infirmary or arranging an appointment with a hospital, and when they do succeed in getting an appointment, they are left to the mercy of the gendarmes to take them to the hospital.”

He added that sometimes prisons did not have a vehicle or personnel to transport inmates. “Sometimes the patients need complicated tests and must go to the hospital many times, which prolongs the whole process and makes it much more complicated.”

Adding that the pandemic has made matters worse, he said sometimes inmates prefered not to go to the hospital to avoid a minimum 14-day quarantine when they returned to the prison. In the meantime when the patient managed to get a a medical report deeming them unfit to remain in prison, the courts refused to act on the report.

Gergerlioğlu pointed out that by the time the prisoner was released, they would have lost a lot of weight and their illness would have worsened considerably.

According to the Human Rights Association (İHD), there are currently 1,605 sick prisoners in Turkish prisons, 604 of whom are critically ill. Although most of the seriously ill patients have forensic and medical reports deeming them unfit to remain in prison, they are not released. Authorities refuse to release them on the grounds that they pose a potential danger to society. In the first eight months of 2020, five critically ill prisoners passed away because they were not released in time to receive proper medical treatment.

Since April four seriously ill prisoners over the age of 70 have died in penal institutions; five inmates suffering from cancer died shortly after they were released; and 16 died of chronic illnesses while imprisoned.