Bayram Kaya, an author and reporter who has been behind bars for 486 days, says what he misses most is covering issues on security, law enforcement and intelligence that he had done for years before government locked him up on farcical charges.

“It was so exciting to be able to touch a keyboard again and write down on computer. I felt what I am missing most is reporting news, he told his visitors from the family. After months later, the authorities in İstanbul’s notorious Silivri Prison allowed him to use the computer once for a week so he can write his defence testimony.

“I would never forget that the sensation I felt for the first time for a long time,” he added.

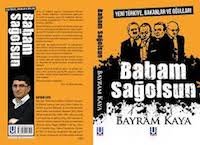

Like many journalists behind bars in Turkey, Kaya is also accused of being a member of FETÖ, a hoax terror organisation that was fabricated by the regime of autocratic President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to persecute the civic Gülen movement. The evidence the public prosecutor presented in the indictment for the alleged terror charges is Kaya’s three published books and his tweet messages.

He faces up to 15-year jail sentence if convicted.

Kaya is a well-respected journalist among his colleagues and have broken many stories especially on public safety, terrorism and national security issues. He was the first journalist who exposed the involvement of the state security elements in the murder of Armenian-Turkish journalist Hrant Dink.

“He has been the jewel of our eyes,” one of his sisters told the Stockholm Centre for Freedom (SCF) when asked about how she knows him, stressing that “Bayram and us were like four peas in a pod. Now our lovely one pea is missing.”

Kaya’s father has done hard labour under tough and hazardous working conditions to provide for his family and create opportunities for the children. Most of the money he had earned at construction sites was spent on kids’ education, something that would help them to move out of the poverty. His parents valued the education so much that the mother had to give up her wedding ring to pay for one of the instalments on the cost of sending Kaya to private tutoring center so he can be better prepared for the competitive state-run university entry examination.

The high score he got in the exam landed him at the Marmara University’s prestigious Department of Journalism from which he would graduate in 2005. The following year, he started his media career as an intern at TRT network, a state broadcaster. In 2007, he moved to London for English language training courses. During his time in London, he had written sports stories for newspapers and magazines in Turkey.

When he returned to İstanbul in 2009, he got a job at Zaman daily which was then the best-selling newspaper of Turkey. He worked his way up, taking assignments on various subjects in different news desks at the paper. He was standing out from the rest and the paper decided to send him to Ankara, the capital where mostly veteran journalists were employed by media outlets. There he covered law enforcement agencies and penned many breaking stories through wide network of sources he had developed very quickly.

Although these books brought a fame and reputation for Kaya, they also invited the wrath of powerful people who were not happy with such exposures. Through his sources, he knew he had been monitored and tracked by the government.

He was the first reporter who got dismissed from the newspaper in Ankara when Erdoğan government unlawfully seized the Zaman daily in March 4, 2016 and replaced its corporate and editorial managements. No compensation or severance payment was made for his abrupt dismissal.

He continued his profession at a newly launched national daily Yeni Hayat, that was established by a group of journalists who were also dismissed by the government from Zaman daily.

Unfortunately, Yeni Hayat daily did not live long and shut down by the government following the controversial coup attempt on July 15, 2016.

Prosecutors have filed numerous lawsuits against him over many of his stories. He even was questioned by the prosecutors whether he was the news source of Cumhuriyet’s then editor-in-chief Can Dündar who published a story on Turkish intelligence trucks carrying illegal arms shipments to Jihadists in Syria in early 2014. He was released pending charges.

After the July 15 events, his detention led to formal arrest by authorities on dubious terror charges. He was placed in İstanbul’s Silivri Prison along with 25 journalists on July 30, 2016. He has been languishing behind bars since then.

The indictment was penned some 7 months after his arrest. Prosecutor presented Kaya’s twitter messages and books as the evidence of terror charges. He was also accused of defaming President Erdoğan’s son Bilal Erdoğan who is not a government official.

The most absurd evidence in the indictment was Kaya’s comments on micro blogging site Twitter. Followings are some examples of his twitter posts which indictment claimed as spreading propaganda of terror:

- Businessmen close to the government avoid paying tax. (July 14, 2016)

- They (the police) detain even handicapped persons and pregnant women. (July 14, 2016)

- President of TUSKON (a businessmen confederation) Rızanur Meral is known for his gentle personality among business circles. ( July 7, 2016)

The hearings in the case of Kaya and 24 other journalists lasted for five days. To the surprise of many, the court decided to release 21 journalists including Kaya at the completion of first hearings.

The moment after the court’s decision was announced, pro-government journalists including ones from Aydın Doğan’s media group, pro Erdoğan trolls and figures in social media kicked off a campaign questioning the journalists’ release.

Before the court’s judgement to release journalists pending trial was executed, the government brought new charges. Thirteen journalists, were told a new investigation on serious allegations of crime was launched against them despite the fact that they had been in prison for 9 months already. A new detention orders issued and they were taken to the police station from the prison cell in a new cycle of processing that led them back to prison again with new added charges.

Another 8 journalists who were ordered to be released were re-arrested after the prosecutor challenged the release order and the judge issued a new arrest warrant within hours without even examining their cases and hearing the defendants’ arguments. Kaya unfortunately was one of these 8 journalists.

Kaya appeared at two successive hearings on April 27, 2017 and July 27, 2017. The court ruled for the continuation of his arrest due to what it claimed the existence of strong suspicion over membership of a terror organisation.

Kaya, father of a 5-year old daughter, will appear once again before judges on December 4, 2017 with a hope that he will be released and reunite with his loved ones this time.

Turkey is the biggest jailer of journalists in the world. The most recent figures documented by the SCF has showed that 256 journalists and media workers are in jails as of November 21, 2017, most in pre-trial detention languishing in notorious Turkish prisons without even a conviction. Of those in Turkish prisons, 230 are arrested pending trial, only 26 journalists remain convicted and serving time in Turkish prisons. An outstanding detention warrants remain for 135 journalists who live in exile or remain at large in Turkey.

Detaining tens of thousands of people over alleged links to the Gülen movement, the government also closed down more than 180 media outlets after the controversial coup attempt.

Turkey survived a controversial military coup attempt on July 15, 2016 that killed 249 people. Immediately after the putsch, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government along with President Erdoğan pinned the blame on the Gülen movement.

Gülen, who inspired the movement, strongly denied having any role in the failed coup and called for an international investigation into it, but President Erdoğan — calling the coup attempt “a gift from God” — and the government initiated a widespread purge aimed at cleansing sympathizers of the movement from within state institutions, dehumanizing its popular figures and putting them in custody.

Turkey has suspended or dismissed more than 150,000 judges, teachers, police and civil servants since July 15. Turkey’s Justice Ministry announced on July 13 that 50,510 people have been arrested and 169,013 have been the subject of legal proceedings on coup charges since the failed coup.