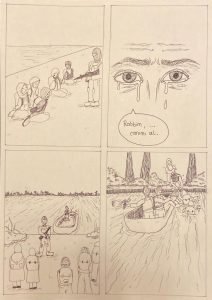

“I left my country, my loved-ones and my life to escape the injustice I had been subjected to,” said Hüsniye, who was sent back to Turkey by Greek authorities on December 12, 2019.

Speaking to the Stockholm Center for Freedom, the former teacher said after hours of walking on dirt paths and enduring freezing weather, they were sent back to Turkey just when they thought they were safe.

“We started our journey to Greece on the morning of December 19,” she said. “We were three men and two women in a boat that crossed the Evros River. After walking for hours through swamps in Greece, we were about to arrive at a police station. We were planning to start our asylum process there, but some 100 meters from the station we were stopped by two military cars.”

Hüsniye said men with black masks they believed to be soldiers stepped out of the car and pointed their guns at them. After a while police officers arrived and took their phones.

“They took our passwords and went through the contents of the phones,” she explained. “Then they put our phones in a bag and left.”

Hüsniye said they tried to explain they were asylum seekers and had fled oppression in Turkey. However, the officers only laughed at them.

Hüsniye was arrested on March 13, 2019 for links to the Gülen movement and was released two months later pending trial. At the time of her arrest Hüsniye had just found out that she was pregnant. However, it was a high risk pregnancy since she was experiencing bleeding. Despite the risk, she wasn’t allowed to use her medication in prison and had a miscarriage while incarcerated.

After her release pending trial Hüsniye was sentenced to six years, three months in prison. She was accused of using the ByLock smartphone application.

ByLock, once widely available online, has been considered a secret tool of communication among supporters of the faith-based Gülen movement since a coup attempt on July 15, 2016, despite the lack of any evidence that ByLock messages were related to the abortive putsch.

The Gülen movement is accused by the Turkish government and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of masterminding the failed coup and is labeled a “terrorist organization,” although the movement denies involvement in the coup attempt or any terrorist activity.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in July 2021 found the use of ByLock not to constitute a criminal offense. However, both Turkey’s Supreme Court of Appeals and the Constitutional Court find the use of ByLock to be sufficient evidence for terrorist organization membership.

The UN Human Rights Council’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention stated in October 2018 that detention, arrest, and conviction based on ByLock use in Turkey violated Articles 19, 21 and 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

After the police officers left, Hüsniye and the others were forced into the military cars and taken to a building that had police cars in front, where the group was searched. Their bags were completely emptied and their belongings were scattered everywhere. At this point Hüsniye said they understood something was terribly wrong and that they were not as safe as they had initially thought.

After an hour they were made to get back into the cars and were taken back to the banks of the Evros River.

“The women were crying, which caused officers to become more visibly angry,” Hüsniye said. “They just shoved one woman to the ground and took her money. I knew we’d also be subjected to that treatment.”

Hüsniye resisted a pat down, but the officer pulled out a knife and pressed it to her belly. He told her he wouldn’t harm her if she gave up her money and whatever was in her bag.

After all the asylum seekers were stripped of their money and personal belongings, they were made to board a boat that took them back to Turkey. They were left on the riverbank at around 2 p.m. and waited until nightfall to get back to safety.

The group was freezing and extremely hungry at this point. They had not even had a sip of water for hours, and a long journey still awaited them. It took them five hours to reach a village, by which time their hands and feet had become numb from the cold.

Hüsniye said she was still suffering from the psychological trauma of the ordeal.

The United Nations Refugee Agency, members of the European Parliament and human rights watchdogs have repeatedly demanded that Greek authorities investigate such incidents of pushback.

According to Amnesty International, the practice of migrant pushbacks in Greece has become so bad that even people who have applied for asylum and have been in the country for some time are being picked up and deported.

EU Home Affairs Commissioner Ylva Johansson during a visit to Greece in March called on the country to “do more” to investigate the allegations. However, Greek Migration Minister Notis Mitarachi denied Greek authorities’ involvement in any kind of pushback.

In an interview with SCF, MEP Tineke Strik said one of the greatest threats facing migrants is pushback at Europe’s external borders. She added that when it came to the most vulnerable asylum seekers, such as women and children, border officers made no exception. “I hear that a lot of women and children are also victims of pushback. When I visited Samos in May, I talked to a Palestinian woman with two small children. She was very frightened because she was part of a larger group that had managed to reach Greece after being pushed back several times. She managed to hide when officers came and put the others in a boat and sent them back to Turkey,” she said.

Strik emphasized that the European Union member states shared responsibility for ensuring a safe and dignified asylum process. “Europe really has good standards, but these standards are not fully achieved. The European Commission is not really enforcing these standards; therefore, we are missing the chance to improve our asylum policy,” she said.

![[Interview] Turkish pushback victim says he was beaten in front of his 5-year-old son and sent back to Turkey migrant](https://stockholmcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Greece_Turkey-border-218x150.jpg)