By Abdullah Bozkurt

The appointment of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan confidante and corrupt politician Şaban Dişli as a non-career ambassador to the Netherlands suggests the Turkish Islamist president is bent on meddling in European affairs through further mobilization of Turkish and Muslim diaspora groups while protecting his secret wealth, which he fears could be frozen or seized abroad.

The move, touted as a sign of the normalization of Turkey’s ties with the Netherlands after the Erdoğan government’s spat with The Hague that forced the Dutch government to bar the visit of a Turkish foreign minister and expel another one to Germany, in fact, spells trouble. It certainly does not qualify as a serious and a sincere step on the part of the Erdoğan government to mend fences with a NATO ally when the designated envoy lacks credentials and credibility to resolve lingering disputes. Rather, it signals that Erdoğan has tapped a man who was already tainted over his alleged role in money laundering and illegal fundraising that involved a controversial Islamist entity in Europe.

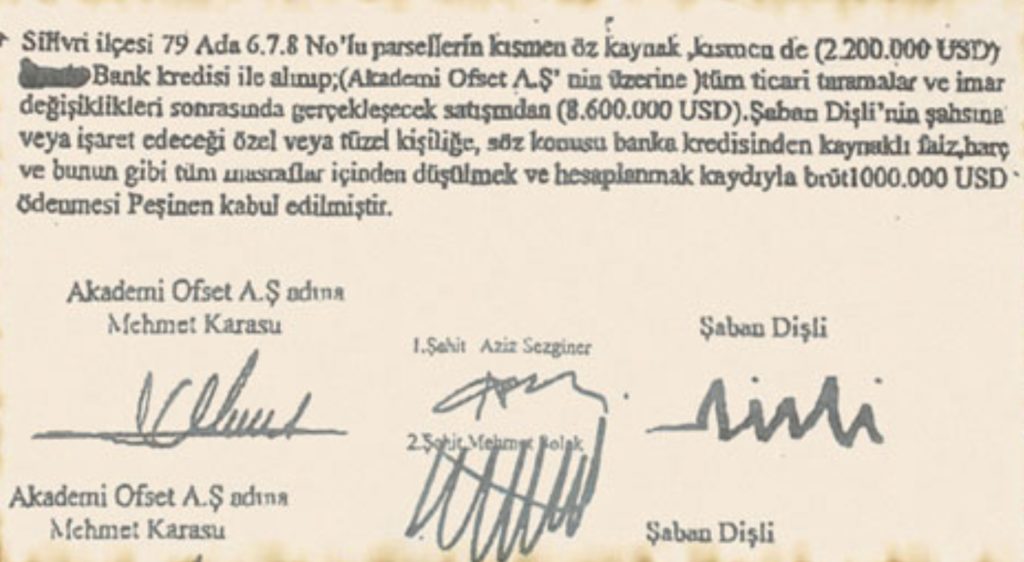

Despite scandalous revelations back in 2008 that Dişli took a million dollar bribe for his role in enacting zoning changes in Istanbul for a retail chain, Erdoğan kept him on his side. A document that was shared on Aug. 11, 2018 with the media by Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, then the parliamentary group deputy chairman of Turkey’s main opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and now leader of the party, clearly indicated that Dişli was promised a kickback in exchange for a land speculation deal that involved the rezoning of property in an Istanbul municipality, controlled by Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP).

He also played a role in securing a bank loan from Deniz Bank for the property. The document, which was signed and notarized in 2006 between Dişli and businessman Mehmet Karasu, chairman of the board of a company called Akademi Ofset A.Ş., secured his share from the deal. The document was also signed by two witnesses identified as Mehmet Solak and Aziz Sezginer, who later had a legal dispute over shares with Karasu, who cheated on the partners. The zoning change on the valuable property that was sold to a company named Tesco-Kipa, a retailer that owns a chain of supermarkets, earned its owners an additional $10 million within 48 hours. Dişli was handsomely reimbursed for his services and his role in making the zoning change happen, both in the Greater Municipality of Istanbul and then in the Silivri City Council, which has jurisdiction over the property in its district.

Following the revelations, Dişli resigned from his position within the party but retained his seat in Parliament, which allowed him to escape prosecution through his parliamentary immunity. Two years later he was implicated in yet another corruption scandal that involved bribing top judges in Turkey. The wiretap records from the investigation revealed that he played a role in influencing members of the Supreme Court of Appeals to manipulate a case concerning a valuable plot of land situated between the Istanbul World Trade Center and the CNR Expo Center near the airport. Nine people including Istanbul Chamber of Trade Chairman Murat Yalçıntaş were detained on charges involving claims that top judges were given TL 1.2 million in bribes so that they would rule against the other party in the dispute, namely the CNR.

Despite the scandals, Erdoğan nominated him again for a parliamentary seat in the 2011 general election, and he was allowed to return to his influential position within the administration of the party. When he could not run for a seat in the 2015 elections because of the three-term limit within the AKP, he was briefly exposed to a bribery prosecution that was previously halted pending waivers for the immunity protection. Yet, Erdoğan again rushed to help him hush up the probe. Prosecutors who were replaced by the Erdoğan government decided to discontinue the investigation and dropped all the charges against him despite overwhelming evidence in the bribery scheme.

In the meantime, he has enjoyed various positions within the party and gained access to the government decision-making apparatus. He served as chief advisor to Erdoğan in 2017 and in the governing party’s Central Decision and Executive Board, a politburo ship tightly run by Erdoğan to control the levers of power in the ruling party. Erdoğan’s strong backing for this man did not change at all even after his brother, Mehmet Dişli, was accused of coup plotting over his alleged key role between coup plotters and then-Chief of General Staff Hulusi Akar, who was reportedly held at gunpoint. The case against his brother is still pending at the Ankara 4th Criminal Court.

Clearly what makes Şaban Dişli so important to Erdoğan is his oft-rumored role in money laundering, kickbacks and corruption schemes that first and foremost benefit his boss, Turkey’s president. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. Both Erdoğan and Dişli have been in the same scheme from day one to siphon off dirty money and enrich themselves by abusing their positions and the authority of the government. Apparently, Dişli’s experience as a banker who worked in the Netherlands for nearly a decade came in handy when Erdoğan set up his government in Turkey and ran his side business to make windfall profits from the abuse of authority. He needed a banker like Dişli who knows how to move his cash around, stash assets in overseas accounts and offshore firms and protect personal wealth accumulated over the years from bribes, kickbacks, and commissions.

There is also another untold story as to why Dişli has been an important operative for Erdoğan. He has been implicated in clandestinely moving funds for Islamist groups in Europe. When German prosecutors indicted several people associated with the Deniz Feneri e.V. charity organization, an Islamist outfit that is closely linked to Erdoğan, Dişli’s name came up in the reporting that covered the scandal, labeled at the time as the biggest charity scandal in German history. Three key suspects were accused of committing fraud in the transfer of donated funds worth 18.6 million euros.

Some of the money that was raised for charitable purposes was diverted to finance media outlet Kanal 7, which is closely aligned with Erdoğan’s AKP, and some ended up in party coffers as well. The Regional Court of Frankfurt am Main convicted three of the charity’s managers for misuse of funds collected as donations. The court also stated that part of the funds had been channeled to entities based in Turkey. However, Erdoğan not only thwarted German prosecutors expansion of their probes to Turkey but also quashed a separate investigation launched by Turkish prosecutors into Deniz Feneri, a Turkish charity that is linked to Germany’s Deniz Feneri e.V. after evidence emerged in the German case.

Deniz Feneri e.V. and Kanal 7 also raised funds in the Netherlands in a charity drive that took place in 2004, and allegations were leveled at the time that some of the money from Dutch taxpayers was also misused just like in Germany. The Federatie van Democratische sociale verenigingen in Nederldan (Federation of Democratic Social Societies in the Netherlands, or FDSS), a Turkish organization in the Netherlands, sent a letter to the Dutch justice minister asking whether an investigation would be launched into Deniz Feneri in the Netherlands The letter was part of a parliamentary question on Nov. 12, 2008 to which Dutch Justice Minister Nebahat Albayrak responded on Dec. 15, 2008, saying that she viewed the German prosecution favorably but found no evidence to launch a similar probe in the Netherlands. She acknowledged receiving the complaint from FDSS and said she would respond in due time.

Moreover, a complaint filed by FDDS with the Rotterdam tax office in 2008 asked Dutch authorities to look into corruption allegations against Dişli, who had worked for a Turkish bank in the Netherlands for nearly a decade. Citing Dişli’s claim of earning one million dollars while he worked in the Netherlands, the letter asked the Dutch tax office whether Dişli had declared such an income with Dutch authorities while he was in the Netherlands and how he was able to transfer such an amount of money to Turkey if he had in fact earned that money in the Netherlands.

Dişli had worked for Demir-Halk Bank (Nederland) N.V., which was established with Turkish capital, and Turkish state lender Halkbank is a major shareholder. The bank’s niche market is the Turkish diaspora in the Netherlands and other parts of Europe. Halkbank was the subject of major corruption probes in Turkey in 2013 that incriminated Erdoğan as well. The Turkish state lender is expected to soon be slapped with a multi-billion dollar fine by the US government for its role in violating US sanctions on Iran. Halkbank’s deputy general manager, Mehmet Hakan Atilla, was convicted by a federal court in New York earlier this year and sentenced to jail time. The case revealed new evidence of how Turkish President Erdoğan was involved in a graft scheme when the prosecution’s key witness, former suspect Reza Zarrab, spilled the beans on how he bribed top government officials in Turkey to make illegal bank transfers using Halkbank.

The appointment of Dişli as ambassador to the Netherlands does not seem to be a part of the rapprochement between the two countries at all. Rather, it feels like Erdoğan tapped Dişli once again to run clandestine business dealings in Europe ranging from financing and mobilization of the Turkish diaspora and Islamist groups to move around Erdoğan family assets stashed in many European cities. This time Dişli has the protection of diplomatic immunity. But again, as seen in the case of expelled Turkish Minister Fatma Betül Sayan Kaya, who tried to hold an illegal rally in Rotterdam under personal orders from Erdoğan in 2016 and the revocation of landing rights for the plane of Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, the Dutch have their own ways and means of undercutting Erdoğan’s long arm operating on its soil.

Dişli’s new clout as a diplomat may turn out to be of not so much use for Erdoğan after all as the Dutch really mean business when they say won’t tolerate interference from Erdoğan, who is hell-bent on stirring up troubles among the 405,000 Turks living in the Netherlands. (turkishminute.com)